I remain confident in the concept and now have a better sense for the media that I’d like to include. In line with your advice in response to last week’s update, I’d like to show, for example, just photographs on the first page. And maybe just headlines on the second. Something intriguing that will pique visitors’ interest and keep them coming.

I am still hunting for sources, and have found fewer on the capitalist side, interestingly, than on the communist. This is a concern, especially since the West did not pour as many resources into their front publications as the Soviet bloc did into theirs. So I’ll keep searching.

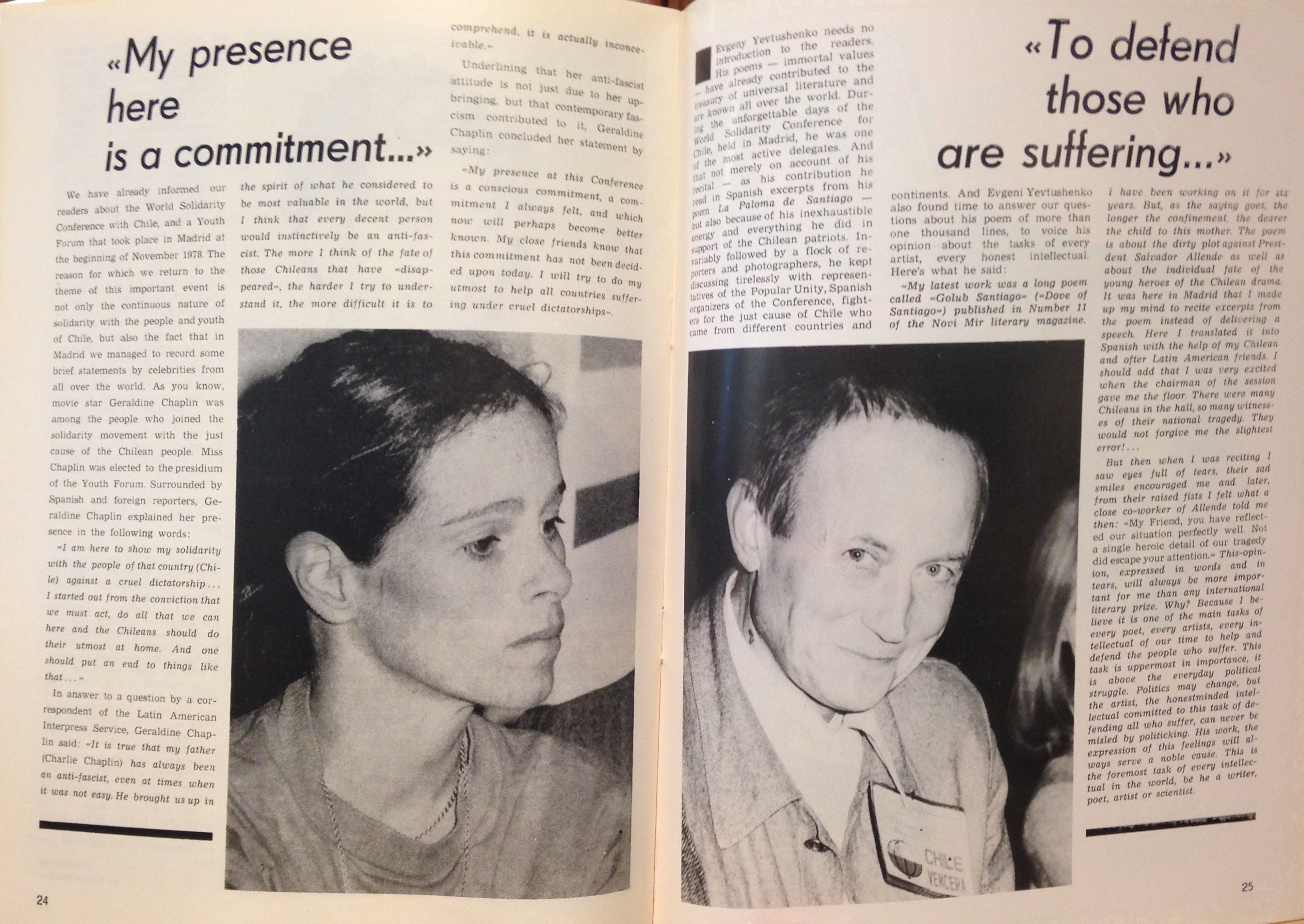

Here is an example of one that I do have, and that I posted to Omeka for Mills Kelly’s class. The resolution on this picture is better than on others, but I’m not sure what the amateurish photography means for the visitor’s experience. Does it make the publication somehow more authentic? Does it make the site seem unprofessional?

The other problem concerns Omeka. I haven’t found any plug-in that will let me let the visitor click on one side or the other and have that input appear on a subsequent page, so that you wind up with a score at the end. If this proves impossible, then I’ll have to just go analog by letting visitors keep a tally themselves, and show them the answers in a final page. I’d prefer to do something flashier, but I don’t have 1/10 the coding skill to make that happen. Which brings me back to the issue of what platform to choose. I’m still wondering, should I just do WordPress? I’ve had trouble with my WordPress version of the site, on the front end. So it’s not as if everything there is easy. But the plugin universe is so much larger there that surely my button-pressing function will be possible. And then there’s the smartmaps option that Carol brought up on the call last week…

All told, I’m behind where I’d like to be. Having reviewed the course calendar, it looks like I won’t put the site on display until July 11, when we show it to classmates. Is that right? In that case I’ll have time to bear down and catch up once things settle down for me–the APs are done and my grades are in. Thanks for your understanding on that.